The Ladybird Book, Wikipedia in Technicolour

09 November 2023

Share

The conveniently pocket sized books that proliferated for a time are not hard for an enthusiast to find.

By Lucy Lethbridge

Lucy Lethbridge is a journalist and writer. She has written several history books, including, most recently, Tourists: How the British Went Abroad to Find Themselves.

Between the 1950s and the 1970s, before the internet, when children watched television for an hour a day, the defining images of a British childhood were found in Ladybird books. Their colourful illustrations were instantly recognisable, they were full of wondrous information and ‘amaze your friends’ skills to master, Ladybirds were the background to mid-twentieth-century growing up. It would be hard to find anyone born before 1980 who wouldn’t pounce delightedly on a battered Ladybird: they are old friends.

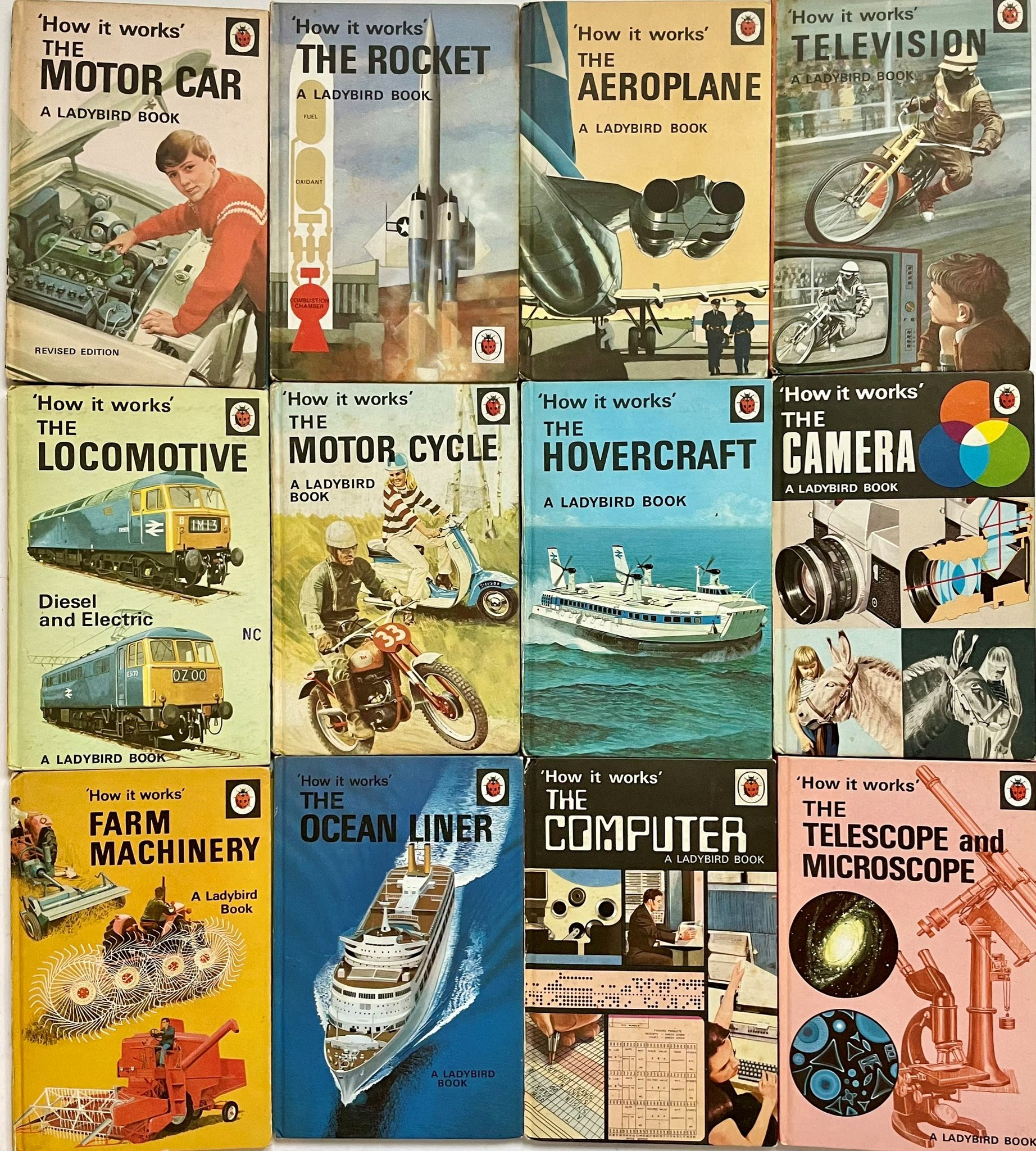

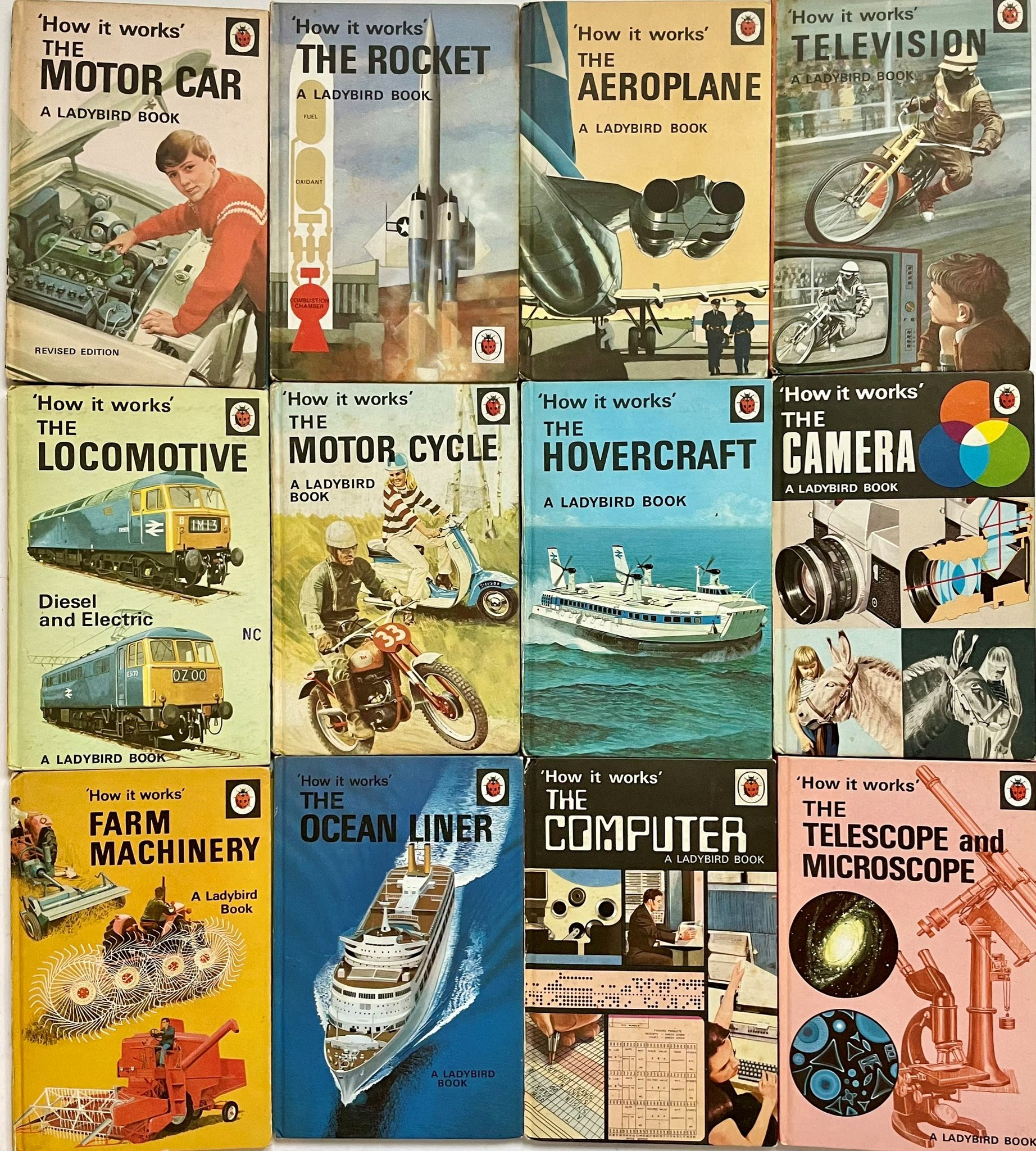

Ladybird titles ran into thousands. There were series on garden birds, fairy tales, kings and queens, shopping with mother, nuclear power and steam locomotion. There is virtually nothing that hasn’t been covered comprehensively but succinctly by a Ladybird book, Wikipedia in technicolour. In the 1960s, the Ministry of Defence even recommended its employees read the ‘Computer’ edition from the Ladybird ‘How it Works’ series.

Some of the 'How it Works' series of ladybird books. Image courtesy of Helen Day.

Some of the 'How it Works' series of ladybird books. Image courtesy of Helen Day.

Ladybirds emerged in Loughborough, from Wills & Hepworth, a printing company which had, since 1914, produced basic, black and white illustrated children’s books under the ‘Ladybird’ imprint. In 1939, the company spotted a market for reassuring stories that chimed with ‘Children’s Hour’ on the wireless. The range was expanded and given a recognisable logo – a ladybird with open wings. The series kicked off in 1940 with ‘Bunnikins’ Picnic Party.’ Wartime paper shortages necessitated the pocket size which would shape the look of Ladybirds for the next three decades.

It was the arrival of the visionary Douglas Keen in 1952 which moved Ladybirds away from Bunnikins and into the cosmos and everything in it. Keen saw that post-war changes in social attitudes about education, a new Education Act, the opening of comprehensive schools and a standardised curricula opened up a new seam of publishing. In 1953, British Birds and their Nests was the first non-fiction Ladybird, illustrated by Allan W Seaby, celebrated for his Japanese-influenced woodcuts of birds. In 1959, the logo was changed to the familiar Ladybird with closed wings. By the time Keen retired in 1972, the year Ladybird was sold to the Pearson group, the imprint had acquired a near impregnable dominion of the bookshelves of British children. But it marked the end of the Ladybird golden age: the imprint still exist, now part of Penguin, but since the early 1980s has sunk in the now hugely competitive children’s book market; their current one-dimensional, computer-inspired illustrations no longer seem original or distinctive. Far more successful recently have been Jason Hazeley’s satirical Ladybirds for nostalgic grownups (‘How it Works: The Dad’; ‘The Story of Brexit’).

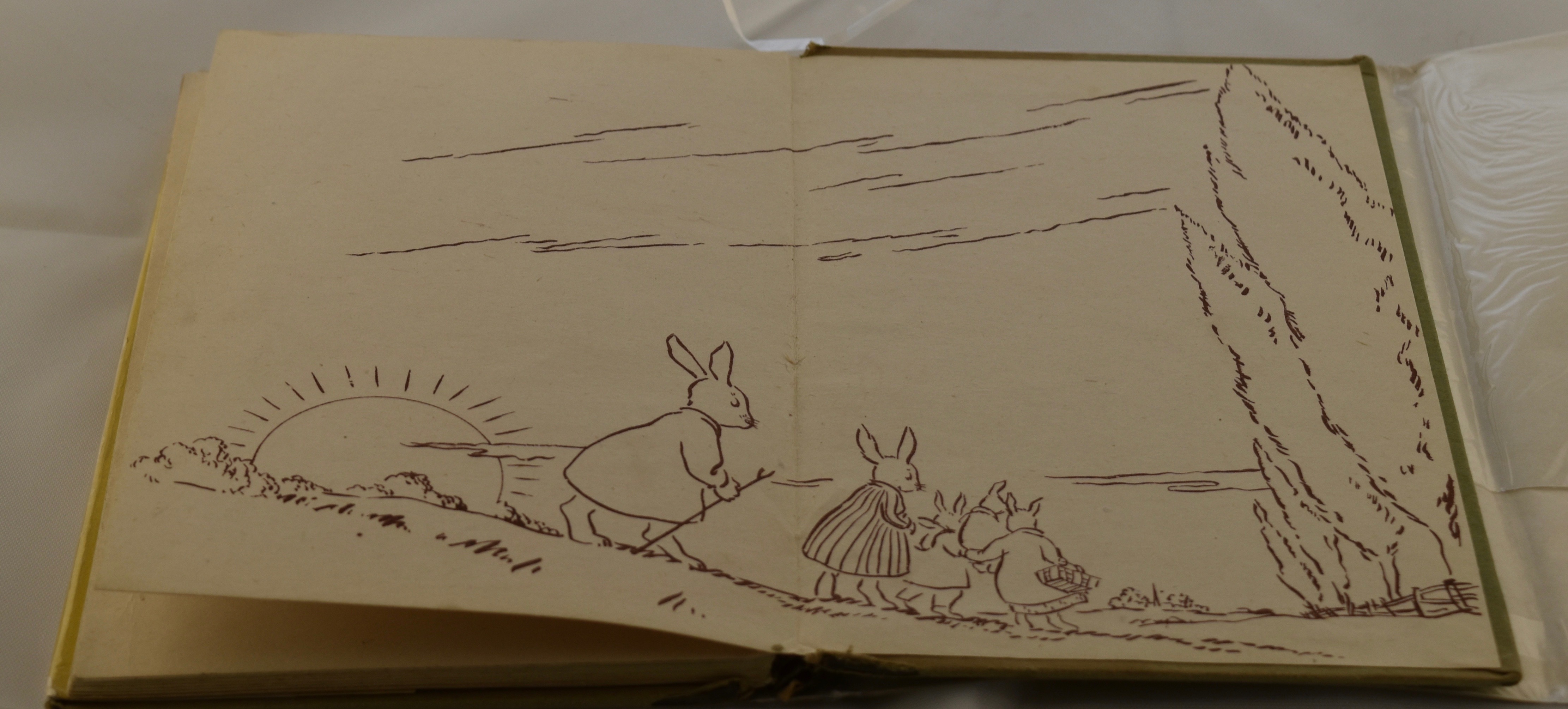

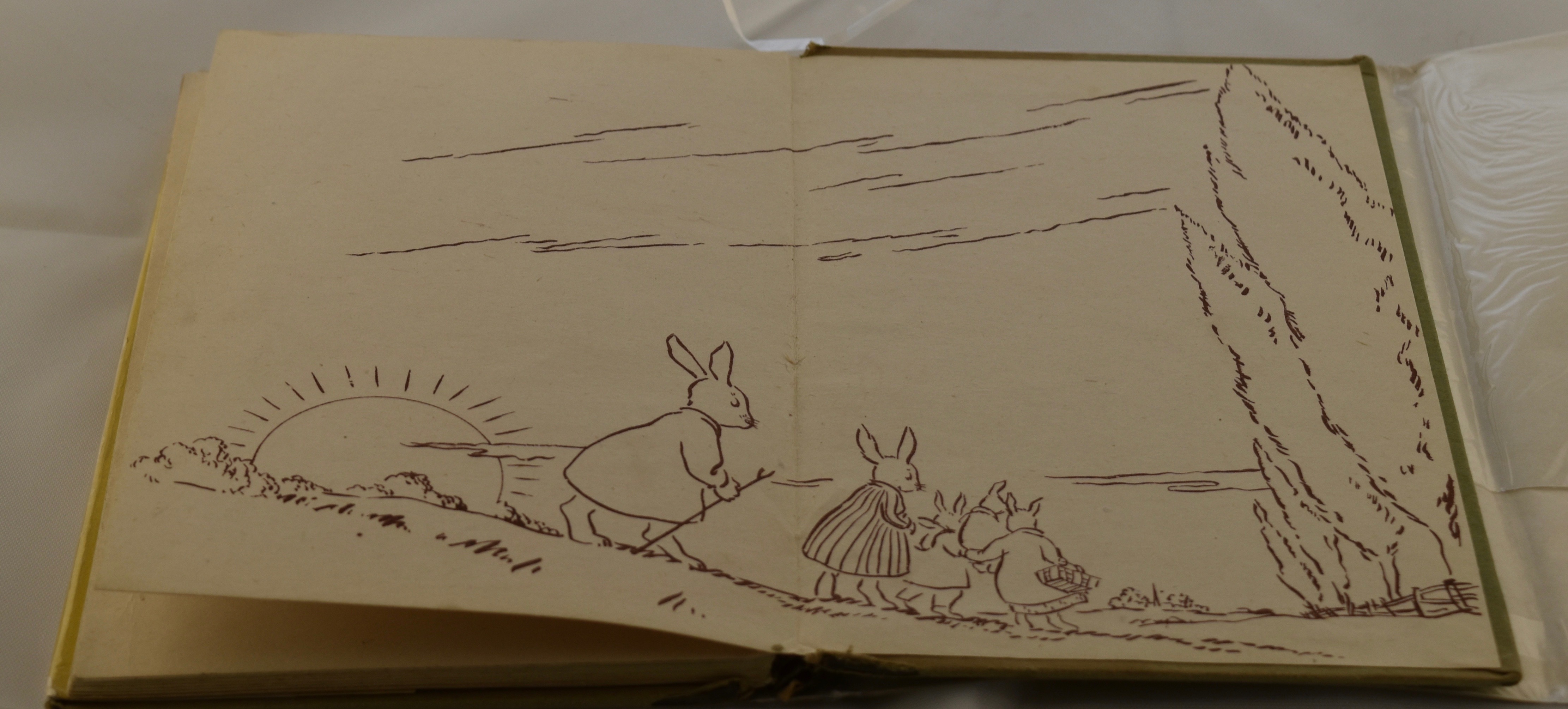

An illustration from 'Bunnikins' Picnic Party'. A copy of the second imprint is currently listed for sale at £125. Image courtesy of the seller.

Ladybirds had such enormous print runs that most are now easy to find for £2 or £3; many collectors will simply enjoy the pleasure of accumulating those coloured spines. Ladybird expert Helen Day (‘I have the collecting gene’), whose website www.ladybirdflyawayhome.com should be the first stop for anyone interested in starting a collection, says that the rare volumes are fiction, particularly those from the 1940s, hard to find in good condition as wartime rationed paper was so fragile. The books in the Tasseltips series, illustrated by Ernest Aris, have rarity value, as does ‘The Adventures of Wonk’ and ‘High Tide’ from the 1940s. Copies of The Impatient Horse (1953) have reached £350. Dating is difficult as Ladybirds don’t follow the antiquarian rules for first editions, instead listing the initial publication date on subsequent editions. Helen Day suggests going by price – and her website provides a useful chart. If the date is 1950 but the price is in 1970s decimal then you have a clue to date. The Ladybird completists’ holy grail, however, is still the brown-paper-covered edition of The Computer: How it Works that was rumoured to have been specially commissioned by the MOD to save its readers’ embarrassment. Is it out there? Helen Day is doubtful but it’s worth keeping an eye out.

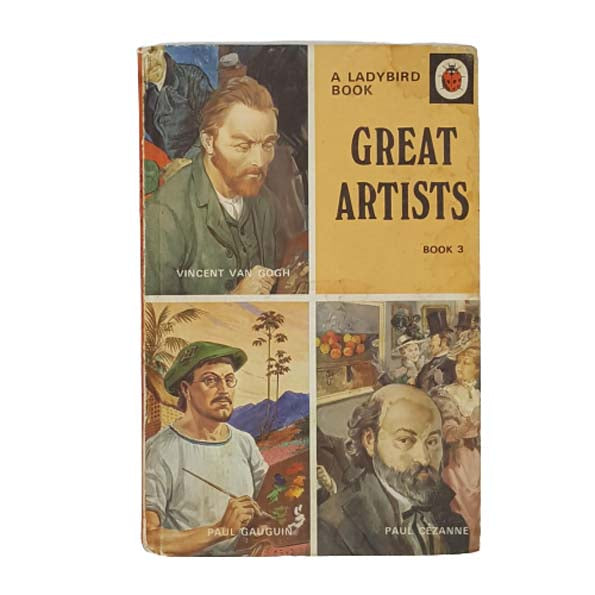

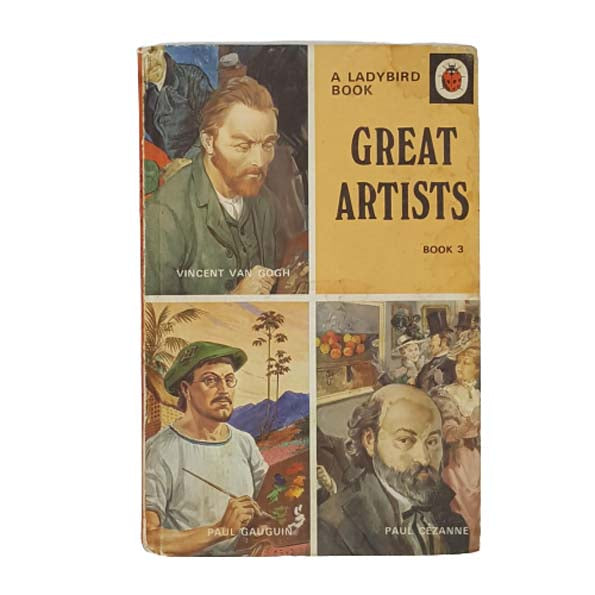

A copy of book three in the Ladybird 'Great Artists' series can be picked up for less than £5. Image courtesy of the seller.

A shelf of Ladybirds is therefore a pleasure but in hardcore collecting terms not perhaps an investment. But what of the original artwork? The list of Ladybird artists is distinguished – and yet, says Helen Day, their work ‘consistently undersells.’ She has picked up pieces for between £25 and £100. The original illustrations, commissioned for a flat fee and returned to the artists when Pearson bought the imprint, were mostly gouache on board. Having gone to the Loughborough factory for print value checking, they were returned to the ownership of the artist in pristine condition. Decorative, figurative and full of detail, it is the magical pictures that make Ladybirds so compelling. And each illustrator brought a distinctive style. As Day puts it: ‘the skills of the artist are perfectly matched to the nature of the composition.’ Douglas Keen was a bold commissioner. Frank Hampson, for example, creator of sci-fi hero Dan Dare, illustrated the nursery rhymes. Ronald Lampitt (Birds and How they Live, What to Look For Inside a Church) had a style quite different from, for example, Martin Aitchison (Peter and Jane) or Charles Tunnicliffe (the What to Look for in … series).

Some of the original artwork is held in the University of Reading which houses the Ladybird collections following the closure of the Wills & Hepworth printing works in 1999 (a bereavement still remembered by those for whom ‘Loughborough was Ladybird’). But there is still ‘a lot out there’ says Helen Day whose travelling exhibition of Ladybird art (currently in Alnwick) is an inspiring place to start. Evocations of everything in the world from elves to cars to kitchens to rockpools: what a glorious thought.

By Lucy Lethbridge

Lucy Lethbridge is a journalist and writer. She has written several history books, including, most recently, Tourists: How the British Went Abroad to Find Themselves.

Between the 1950s and the 1970s, before the internet, when children watched television for an hour a day, the defining images of a British childhood were found in Ladybird books. Their colourful illustrations were instantly recognisable, they were full of wondrous information and ‘amaze your friends’ skills to master, Ladybirds were the background to mid-twentieth-century growing up. It would be hard to find anyone born before 1980 who wouldn’t pounce delightedly on a battered Ladybird: they are old friends.

Ladybird titles ran into thousands. There were series on garden birds, fairy tales, kings and queens, shopping with mother, nuclear power and steam locomotion. There is virtually nothing that hasn’t been covered comprehensively but succinctly by a Ladybird book, Wikipedia in technicolour. In the 1960s, the Ministry of Defence even recommended its employees read the ‘Computer’ edition from the Ladybird ‘How it Works’ series.

Some of the 'How it Works' series of ladybird books. Image courtesy of Helen Day.

Some of the 'How it Works' series of ladybird books. Image courtesy of Helen Day.Ladybirds emerged in Loughborough, from Wills & Hepworth, a printing company which had, since 1914, produced basic, black and white illustrated children’s books under the ‘Ladybird’ imprint. In 1939, the company spotted a market for reassuring stories that chimed with ‘Children’s Hour’ on the wireless. The range was expanded and given a recognisable logo – a ladybird with open wings. The series kicked off in 1940 with ‘Bunnikins’ Picnic Party.’ Wartime paper shortages necessitated the pocket size which would shape the look of Ladybirds for the next three decades.

It was the arrival of the visionary Douglas Keen in 1952 which moved Ladybirds away from Bunnikins and into the cosmos and everything in it. Keen saw that post-war changes in social attitudes about education, a new Education Act, the opening of comprehensive schools and a standardised curricula opened up a new seam of publishing. In 1953, British Birds and their Nests was the first non-fiction Ladybird, illustrated by Allan W Seaby, celebrated for his Japanese-influenced woodcuts of birds. In 1959, the logo was changed to the familiar Ladybird with closed wings. By the time Keen retired in 1972, the year Ladybird was sold to the Pearson group, the imprint had acquired a near impregnable dominion of the bookshelves of British children. But it marked the end of the Ladybird golden age: the imprint still exist, now part of Penguin, but since the early 1980s has sunk in the now hugely competitive children’s book market; their current one-dimensional, computer-inspired illustrations no longer seem original or distinctive. Far more successful recently have been Jason Hazeley’s satirical Ladybirds for nostalgic grownups (‘How it Works: The Dad’; ‘The Story of Brexit’).

An illustration from 'Bunnikins' Picnic Party'. A copy of the second imprint is currently listed for sale at £125. Image courtesy of the seller.

Ladybirds had such enormous print runs that most are now easy to find for £2 or £3; many collectors will simply enjoy the pleasure of accumulating those coloured spines. Ladybird expert Helen Day (‘I have the collecting gene’), whose website www.ladybirdflyawayhome.com should be the first stop for anyone interested in starting a collection, says that the rare volumes are fiction, particularly those from the 1940s, hard to find in good condition as wartime rationed paper was so fragile. The books in the Tasseltips series, illustrated by Ernest Aris, have rarity value, as does ‘The Adventures of Wonk’ and ‘High Tide’ from the 1940s. Copies of The Impatient Horse (1953) have reached £350. Dating is difficult as Ladybirds don’t follow the antiquarian rules for first editions, instead listing the initial publication date on subsequent editions. Helen Day suggests going by price – and her website provides a useful chart. If the date is 1950 but the price is in 1970s decimal then you have a clue to date. The Ladybird completists’ holy grail, however, is still the brown-paper-covered edition of The Computer: How it Works that was rumoured to have been specially commissioned by the MOD to save its readers’ embarrassment. Is it out there? Helen Day is doubtful but it’s worth keeping an eye out.

A copy of book three in the Ladybird 'Great Artists' series can be picked up for less than £5. Image courtesy of the seller.

A shelf of Ladybirds is therefore a pleasure but in hardcore collecting terms not perhaps an investment. But what of the original artwork? The list of Ladybird artists is distinguished – and yet, says Helen Day, their work ‘consistently undersells.’ She has picked up pieces for between £25 and £100. The original illustrations, commissioned for a flat fee and returned to the artists when Pearson bought the imprint, were mostly gouache on board. Having gone to the Loughborough factory for print value checking, they were returned to the ownership of the artist in pristine condition. Decorative, figurative and full of detail, it is the magical pictures that make Ladybirds so compelling. And each illustrator brought a distinctive style. As Day puts it: ‘the skills of the artist are perfectly matched to the nature of the composition.’ Douglas Keen was a bold commissioner. Frank Hampson, for example, creator of sci-fi hero Dan Dare, illustrated the nursery rhymes. Ronald Lampitt (Birds and How they Live, What to Look For Inside a Church) had a style quite different from, for example, Martin Aitchison (Peter and Jane) or Charles Tunnicliffe (the What to Look for in … series).

Some of the original artwork is held in the University of Reading which houses the Ladybird collections following the closure of the Wills & Hepworth printing works in 1999 (a bereavement still remembered by those for whom ‘Loughborough was Ladybird’). But there is still ‘a lot out there’ says Helen Day whose travelling exhibition of Ladybird art (currently in Alnwick) is an inspiring place to start. Evocations of everything in the world from elves to cars to kitchens to rockpools: what a glorious thought.