Feminist Literature

07 December 2023

Share

The gender pay-gap in the world of antiquarian books.

by Francesca Peacock

If Margaret Cavendish; the 17th century Duchess of Newcastle and polymath, poet, philosopher, and scientist, had been in New York in December 2022, she may well have had the shock of a lifetime. Not just for the obvious reasons (she would have to be a well-preserved 400 years old, or a spectral ghost), but for something rather more exciting. As she swanned into Christie’s in the Rockefeller Plaza, she would have seen one of her own books on sale: a first edition of her first volume, Poems and Fancies (1653).

This edition has been well-looked after, and well-loved. Its title page bears two hand-written inscriptions of ownership: the first, an “Elizabeth Pain” on the “13th January 16?3”, and the second, nearly a century later, “Elias Harry Paine and Mary Paine, their book 1747”. Cavendish may well have been delighted to know that her book — the book that got her the reputation of being mad; more insane than the “soberer people in Bedlam” — was still being valued in the century after her death. But, she would have been infinitely more excited to know that, in December last year, that very same book sold for no less than $30,240 — nearly three times its estimate sale price of between $8000 and $12,000.

Just seven years ago – in 2015 – an edition of the same book in a comparable condition, sold for only $2750. Back in 2011, a collection of five of her works from across her career had an estimate between £6,000 and £8,000.

Poems and Fancies by Margaret Cavendish, a group of 5 volumes that was offered by Sotheby's with an estimate of £6,000-8,000.

What on earth has happened, then, to the valuation of Margaret Cavendish’s works? Her fortune is, in fact, part of a broader picture of the increasing price for early modern women’s writing. In the same lot that saw Poems and Fancies reach over $30,000, a first edition of Katherine Philips’s work — the 17th century Royalist poet and Cavendish’s contemporary — reached some $13,860. In 2016, another copy of the very same edition, fetched only £900.

It’s a picture of commercial value increasing which can be echoed for almost every other women early modern writer, from Aphra Behn (a collection of poems sold in 2008 for £750; individual plays now reach over £6,000), to, a century later, Mary Wollstonecraft. In 2018, a copy of her ground-breaking work of feminist thought, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman sold for over £10,000. At the turn of the millennium, the same work reached only £1,840.

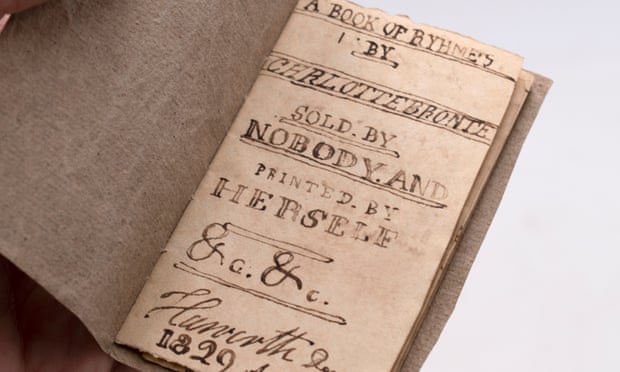

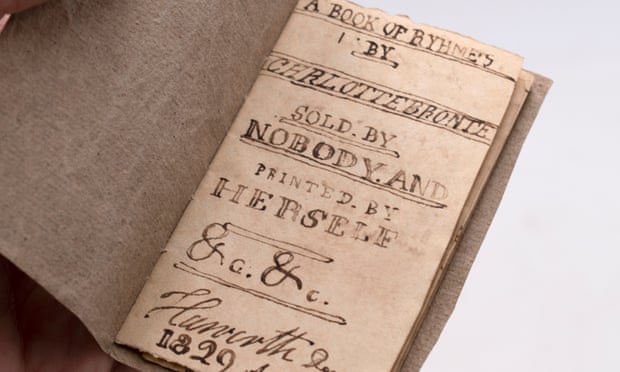

Indeed, if other women’s writing is anything to go by, the sky is the limit with auction prices: just in September 2021, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein went for $1.17 million — the most ever paid for a printed work by a woman. A year later in 2022, a small book of handwritten, previously unseen “ryhmes” by Charlotte Brontë went for $1.25 million.

'A Book of Ryhmes' by Charlotte Brontë. Image courtesy of James Cummins Bookseller.

There’s evidently a gulf between these record-breaking figures — books by some of the largest female names in the literary canon — and the smaller sums reached by the likes of Margaret Cavendish, but what do these increases in value mean?

The increase in value speaks to a greater interest in historic women’s writing more generally. For Margaret Cavendish, collectors are paying more for her works just as she has become, rightly, a “hot” academic topic, and as discussions of ground-breaking nature (she was, amongst other “firsts”, the author of the inaugural work of science fiction — The Blazing World). Finally, her work — and that by other early modern women who were so brave to publish their work — is being valued by collectors.

But, it’s too easy to tie monetary value to literary and critical importance. In the art world, this assumption that has long seen art by women thought to be less “good”. It’s a recognised phenomenon, the art world’s gender pay gap and self-perpetuating cycle; the price ticket attached to the art becomes a short-hand for its artistic merit and the factors which have influenced it — the historic undervaluing of women’s work — are ignored.

Does the increase in value of these women’s books suggest that the rare book market has avoided this issue? Unfortunately not. Even while the price for women’s writing is increasing, it is still nowhere as high as the auction records for men’s writing: in a list of over 150 books sold at auction for over a million dollars, women author’s names — six, in total — are rare enough to count on your fingers. Financially, at least, women’s writing is still nowhere near as valued as that by men. But, of course, for all that the record-breaking price reached by Frankenstein pales in comparison to some of the prices reached by men’s books, nobody could argue that Mary Shelley’s work was not incredibly important; a seismic contribution to literature. With books, as with art, there’s always a judgement beyond the monetary.

And, for every story of an increase in value — Margaret Cavendish’s upturned fortunes, or Katherine Philips’s — there’s a story of jaw-droppingly-low prices. Currently for sale on Oxfam is a copy of Charlotte Smith’s Elegiac Sonnets — poems written in the last two decades of the 18th century, beloved by writers from William Wordsworth to John Keats. It’s a slightly battered copy of the sixth edition (Charlotte saw ten editions of her poems published in her life-time; she was incredibly popular) but it is still only selling for £100. It is hard to think what other antique or artefact from the 18th century would sell for that little, not least one which includes sonnets that Samuel Taylor Coleridge described as “creating a sweet and indissoluble union between the intellectual and the material world”.

From Cavendish to Charlotte Smith — now might well be the time to snap up some literary bargains, before their prices rise even more. But, just don’t take any bargains you come by as proof of their lesser literary merit.

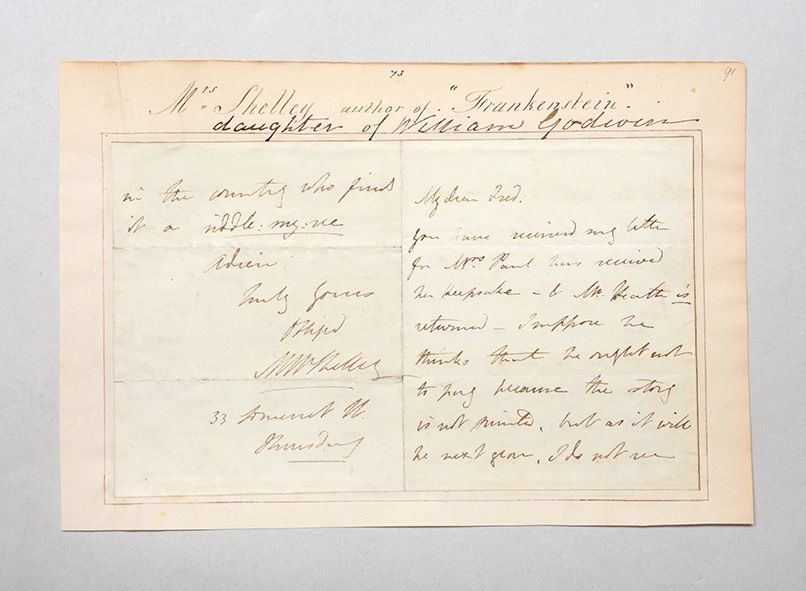

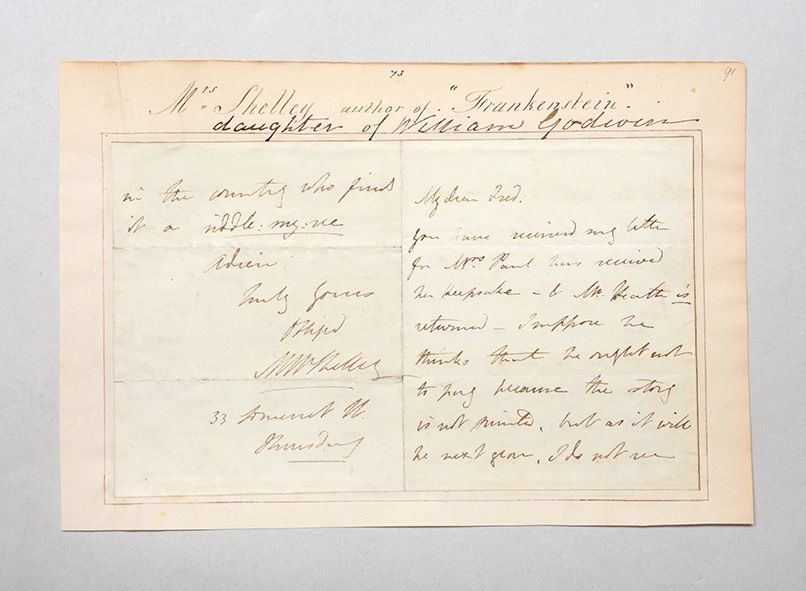

Mary Shelley's letters are also collected. This autograph letter signed to Frederic Mansel Reynolds is offered by Peter Harrington Rare Books.

by Francesca Peacock

If Margaret Cavendish; the 17th century Duchess of Newcastle and polymath, poet, philosopher, and scientist, had been in New York in December 2022, she may well have had the shock of a lifetime. Not just for the obvious reasons (she would have to be a well-preserved 400 years old, or a spectral ghost), but for something rather more exciting. As she swanned into Christie’s in the Rockefeller Plaza, she would have seen one of her own books on sale: a first edition of her first volume, Poems and Fancies (1653).

This edition has been well-looked after, and well-loved. Its title page bears two hand-written inscriptions of ownership: the first, an “Elizabeth Pain” on the “13th January 16?3”, and the second, nearly a century later, “Elias Harry Paine and Mary Paine, their book 1747”. Cavendish may well have been delighted to know that her book — the book that got her the reputation of being mad; more insane than the “soberer people in Bedlam” — was still being valued in the century after her death. But, she would have been infinitely more excited to know that, in December last year, that very same book sold for no less than $30,240 — nearly three times its estimate sale price of between $8000 and $12,000.

Just seven years ago – in 2015 – an edition of the same book in a comparable condition, sold for only $2750. Back in 2011, a collection of five of her works from across her career had an estimate between £6,000 and £8,000.

Poems and Fancies by Margaret Cavendish, a group of 5 volumes that was offered by Sotheby's with an estimate of £6,000-8,000.

What on earth has happened, then, to the valuation of Margaret Cavendish’s works? Her fortune is, in fact, part of a broader picture of the increasing price for early modern women’s writing. In the same lot that saw Poems and Fancies reach over $30,000, a first edition of Katherine Philips’s work — the 17th century Royalist poet and Cavendish’s contemporary — reached some $13,860. In 2016, another copy of the very same edition, fetched only £900.

It’s a picture of commercial value increasing which can be echoed for almost every other women early modern writer, from Aphra Behn (a collection of poems sold in 2008 for £750; individual plays now reach over £6,000), to, a century later, Mary Wollstonecraft. In 2018, a copy of her ground-breaking work of feminist thought, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman sold for over £10,000. At the turn of the millennium, the same work reached only £1,840.

Indeed, if other women’s writing is anything to go by, the sky is the limit with auction prices: just in September 2021, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein went for $1.17 million — the most ever paid for a printed work by a woman. A year later in 2022, a small book of handwritten, previously unseen “ryhmes” by Charlotte Brontë went for $1.25 million.

'A Book of Ryhmes' by Charlotte Brontë. Image courtesy of James Cummins Bookseller.

There’s evidently a gulf between these record-breaking figures — books by some of the largest female names in the literary canon — and the smaller sums reached by the likes of Margaret Cavendish, but what do these increases in value mean?

The increase in value speaks to a greater interest in historic women’s writing more generally. For Margaret Cavendish, collectors are paying more for her works just as she has become, rightly, a “hot” academic topic, and as discussions of ground-breaking nature (she was, amongst other “firsts”, the author of the inaugural work of science fiction — The Blazing World). Finally, her work — and that by other early modern women who were so brave to publish their work — is being valued by collectors.

But, it’s too easy to tie monetary value to literary and critical importance. In the art world, this assumption that has long seen art by women thought to be less “good”. It’s a recognised phenomenon, the art world’s gender pay gap and self-perpetuating cycle; the price ticket attached to the art becomes a short-hand for its artistic merit and the factors which have influenced it — the historic undervaluing of women’s work — are ignored.

Does the increase in value of these women’s books suggest that the rare book market has avoided this issue? Unfortunately not. Even while the price for women’s writing is increasing, it is still nowhere as high as the auction records for men’s writing: in a list of over 150 books sold at auction for over a million dollars, women author’s names — six, in total — are rare enough to count on your fingers. Financially, at least, women’s writing is still nowhere near as valued as that by men. But, of course, for all that the record-breaking price reached by Frankenstein pales in comparison to some of the prices reached by men’s books, nobody could argue that Mary Shelley’s work was not incredibly important; a seismic contribution to literature. With books, as with art, there’s always a judgement beyond the monetary.

And, for every story of an increase in value — Margaret Cavendish’s upturned fortunes, or Katherine Philips’s — there’s a story of jaw-droppingly-low prices. Currently for sale on Oxfam is a copy of Charlotte Smith’s Elegiac Sonnets — poems written in the last two decades of the 18th century, beloved by writers from William Wordsworth to John Keats. It’s a slightly battered copy of the sixth edition (Charlotte saw ten editions of her poems published in her life-time; she was incredibly popular) but it is still only selling for £100. It is hard to think what other antique or artefact from the 18th century would sell for that little, not least one which includes sonnets that Samuel Taylor Coleridge described as “creating a sweet and indissoluble union between the intellectual and the material world”.

From Cavendish to Charlotte Smith — now might well be the time to snap up some literary bargains, before their prices rise even more. But, just don’t take any bargains you come by as proof of their lesser literary merit.

Mary Shelley's letters are also collected. This autograph letter signed to Frederic Mansel Reynolds is offered by Peter Harrington Rare Books.