Dora Carrington: Beyond Bloomsbury

03 January 2025

Share

by Lucy Lethbridge

Lucy Lethbridge is a journalist and writer. She has written several history books, including, most recently, Tourists: How the British Went Abroad to Find Themselves.

Crop-haired, coltishly boyish, energetically creative and friend and lover of both men and women, Dora Carrington (she dropped the Dora early on and was known simply as Carrington) was the very embodiment of the Bloomsbury Group spirit and the jazzy bohemianism that flourished in the inter-war years. As is the case with so many of the Bloomsberries, Carrington’s biography tends to overshadow her work and she is often viewed as an artist on the edge of the group rather than in the central space her works deserve.

Her life was free-spirited and buffeted and romantic without a trace of sentimentality and often marked by sadness. And her end was tragic. She ran away from her kindly father and a mother who was an enthusiast for martyrdom and respectability, to study at the Slade, just before the First World War, part of the generation of young artists described by their tutor Henry Tonks as ‘a crisis of brilliance.’ Among her fellow students was Mark Gertler, who became her lover and whose paintings at this period (though darker and stranger than Carrington’s) echo hers.

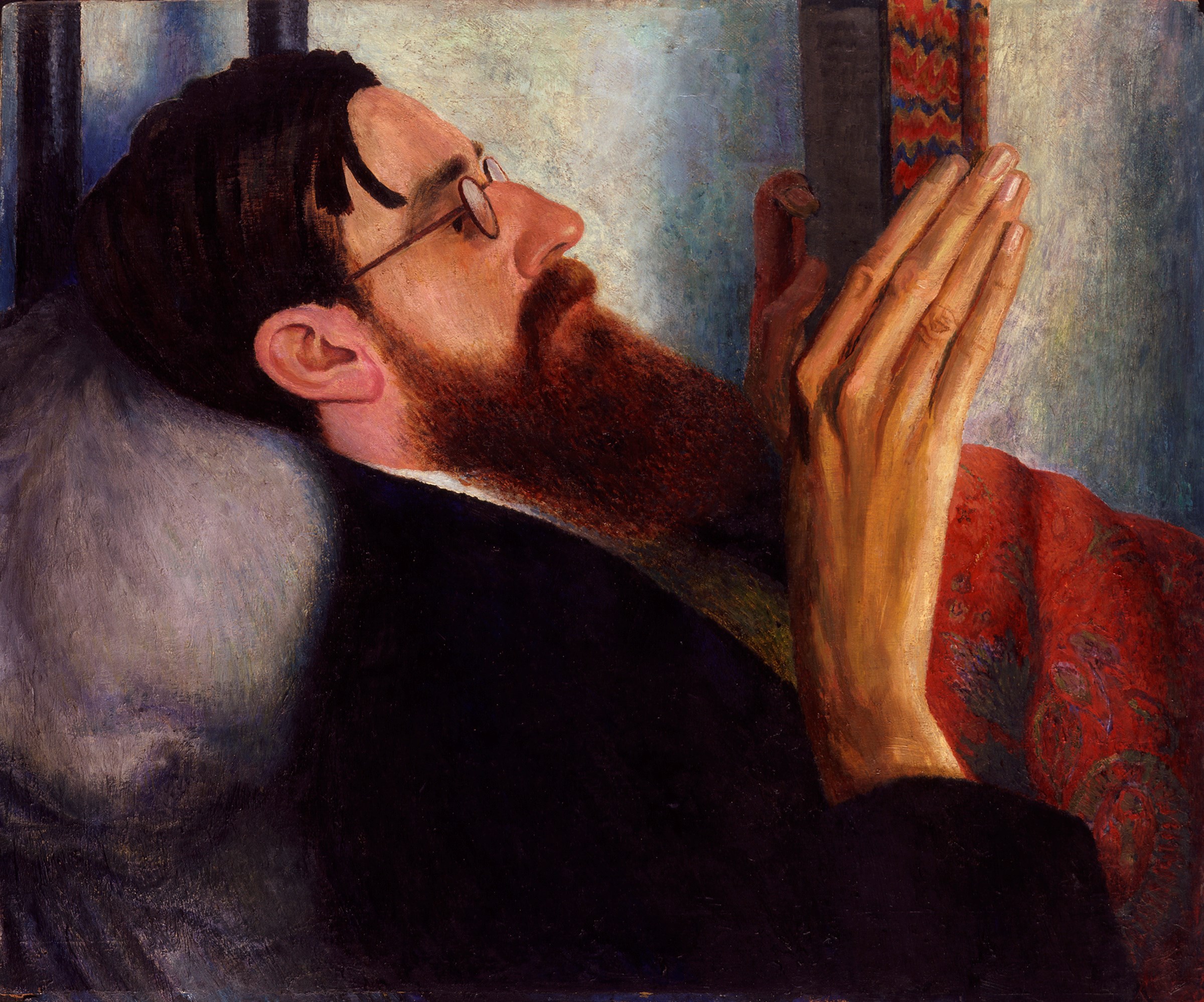

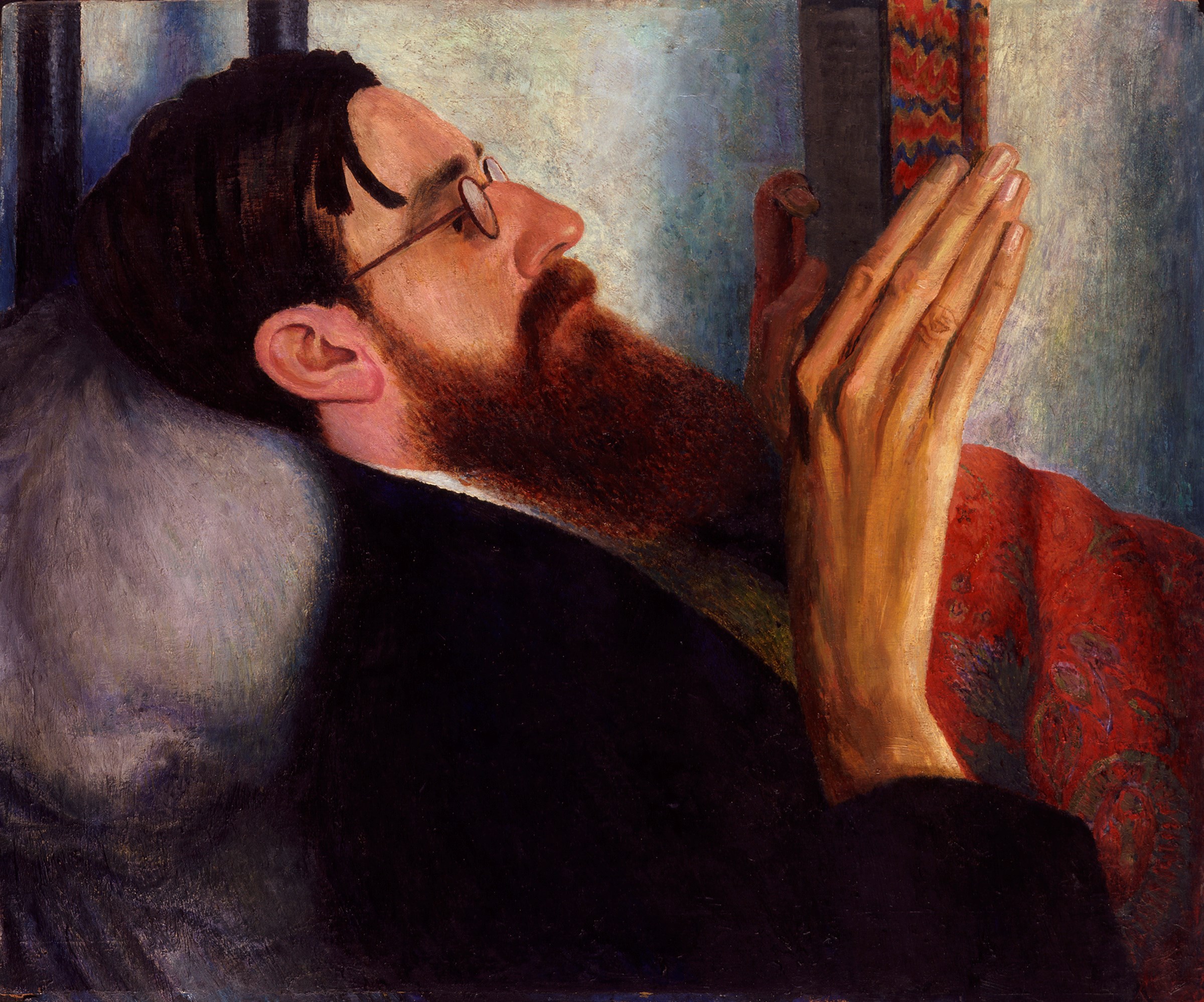

Dora Carrington, Lytton Strachey Reading, 1916, Oil on panel

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Carrington took her prodigious talent for draughtsmanship, modelling and still life out into the world and was soon swept up in the convention-defying and convivial excitements of life in the Bloomsbury Group. And she might (who knows?) then have moved on to different worlds entirely were it not that, while staying with Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant at Asheham in Sussex, she crept upstairs to cut fellow guest Lytton Strachey’s beard off. Legend has it that he opened his eyes and she fell instantly in love. From that moment, Strachey was the lodestone of Carrington’s life. He was gay so their relationship was cosily domestic but non-sexual. She had many lovers and eventually married Ralph Partridge, a writer and sportsman, with whom Lytton was also in love. Their menage a trois (‘a triangular trinity of happiness’), much of it at Ham Spray, their Hampshire house, was a time of great happiness and stability but was shattered when Lytton died in 1932. Unable to continue without him, two weeks later Carrington took her own life. She was only 39.

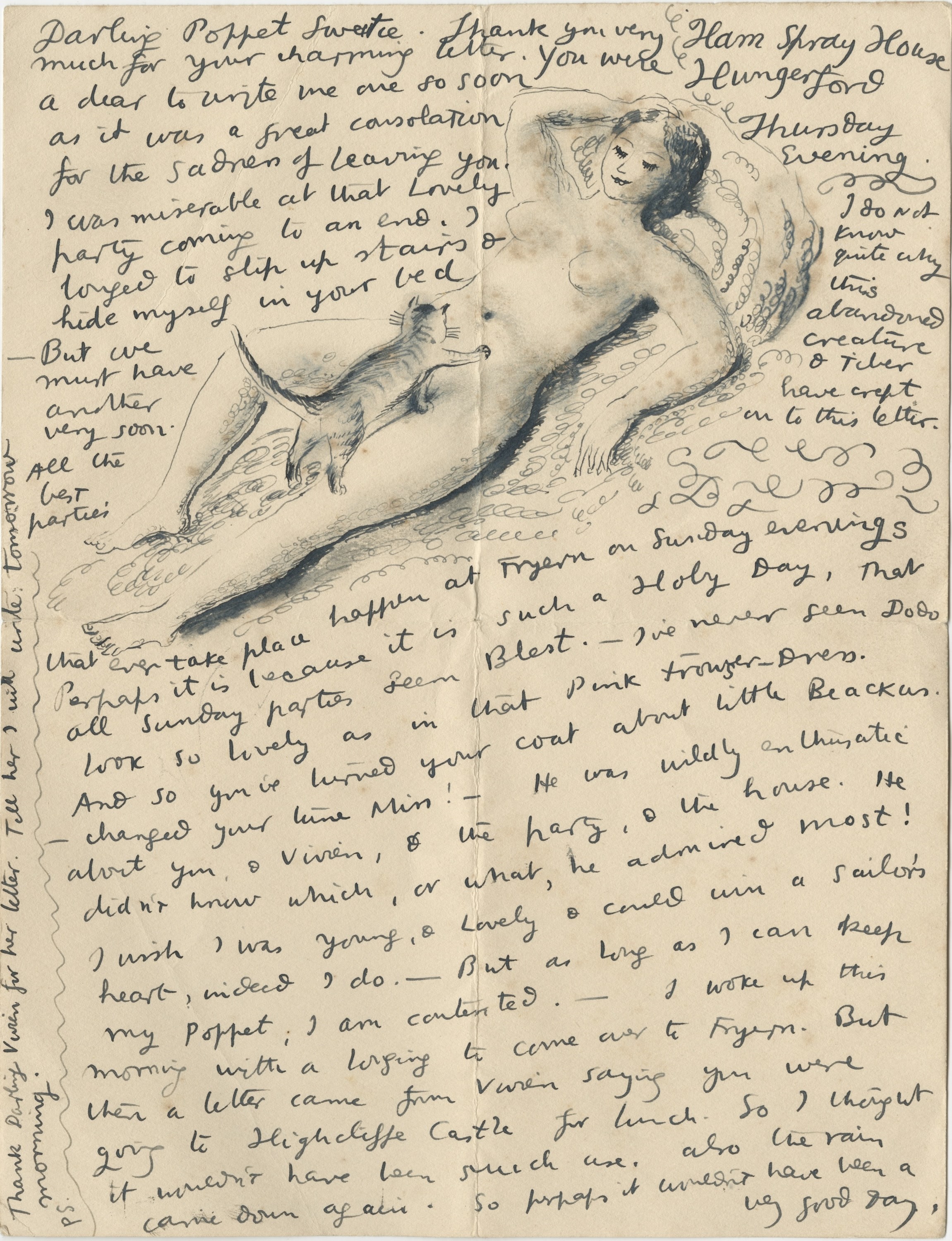

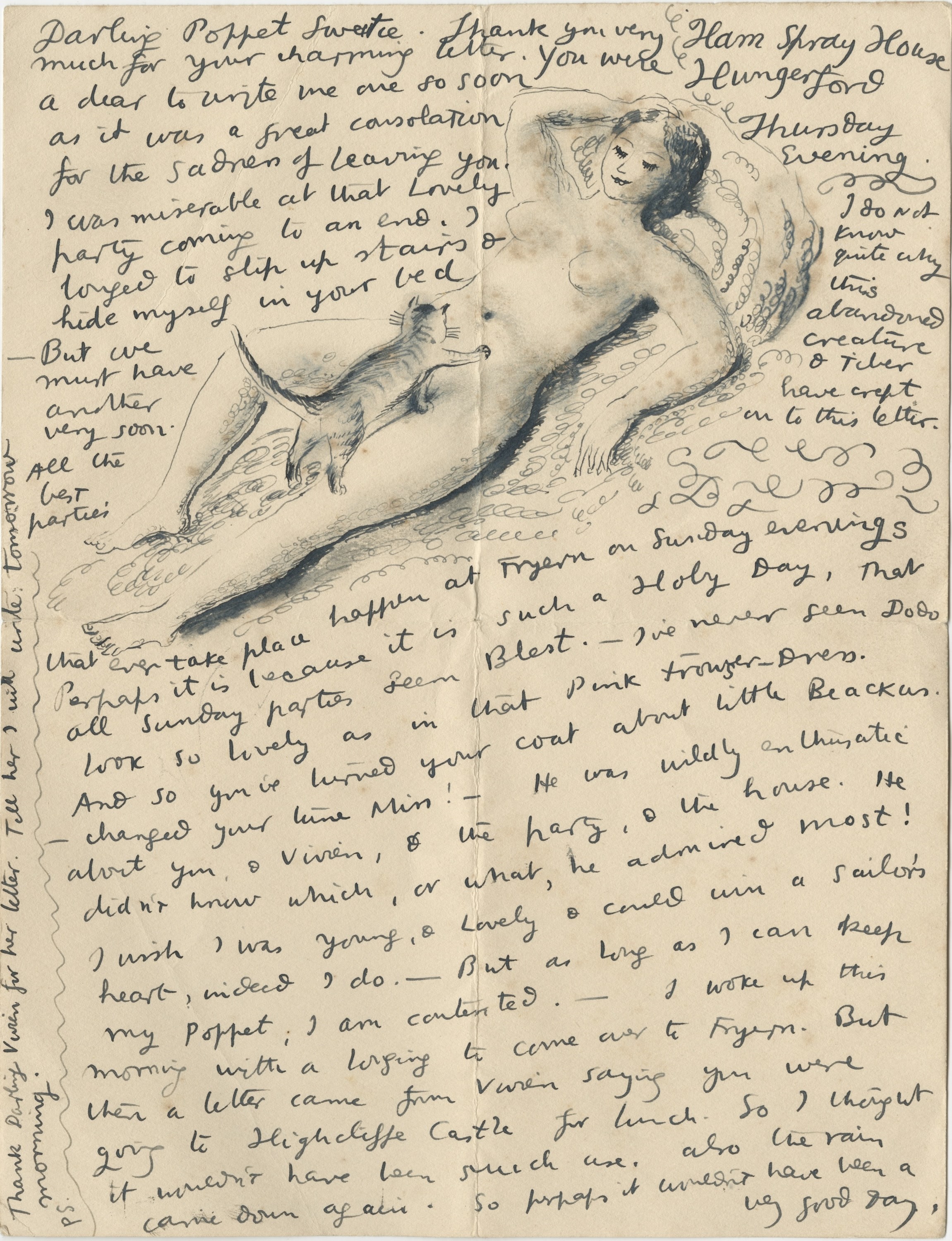

Dora Carrington, Cat and nude, illustrated letter to Poppet John, 1928.

Dora Carrington, Cat and nude, illustrated letter to Poppet John, 1928.

Courtesy of the Dora Carrington Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

A wonderful new exhibition at the Pallant House gallery in Chichester has put Carrington’s art back into the foreground. And not just her paintings but all the teeming creativity that characterised her whole life: her misspelt letters illustrated with wonderful sketches of life at Ham Spray or cartoonish pictures in the margins; the furniture she painted with brightly theatrical scenes; a fireplace decorated with her painted tiles; a trompe l’oeil bookcase filled with books with funny titles (‘Deception’ by Jane Austen being one). She had a profitable sideline making tinsel pictures (in the tradition of Victorian ‘treacle’ paintings) on glass which she sold in Fortnum & Mason – she would feed her guests sweets and hoard the coloured sweet papers. Very few of these pictures have survived but the show’s curators, Ariane Bankes and Anne Chisholm (editor of Carrington’s letters) have scoured the country and come up with some delightful examples, displaying Carrington’s love for popular and folk art, for pantomime, circus, and Victorian ephemera. One of Carrington’s tinsel pictures sold at Bonhams in 2021 for £57,000. She would have been mightily surprised and, I think, amused to know this.

Dora Carrington, Iris Tree on a Horse, c.1920s, oil, ink, silver foil & mixed media on glass, The Ingram Collection.

Dora Carrington, Iris Tree on a Horse, c.1920s, oil, ink, silver foil & mixed media on glass, The Ingram Collection.

Courtesy of The Ingram Collection.

Carrington’s paintings are lovely, compelling, sometimes intimate (her well-known portrait of Strachey, his long-fingered hands holding a book to his nose, is here) and sometimes shadowed by a kind of foreboding – such as ‘Farm at Watendlath’, her oil of a white farmhouse in Cumbria surrounded by hills that bear in oppressively. Like Gertler, she was influenced by pub-signs, with their flat, colourful one-dimensionality and this is apparent in many of her portraits: she liked the solid- planed beauty of her housemaid Annie Stiles and painted her portrait several times. And ‘Mrs Box’ is a portrait of the housekeeper who looked after the Cornish house where the Carrington family went on holiday. Foursquare, her hands on her lap, her old-fashioned bonnet surrounding an impenetrable old face, ‘Mrs Box’ portrait seems a remarkable achievement for a 20-year-old.

Dora Carrington, Mrs Box, 1919, Oil on canvas.

Dora Carrington, Mrs Box, 1919, Oil on canvas.

Courtesy of The Higgins Bedford.

Known works by Carrington are few – but many are now integral to the visual chronicles of Bloomsbury. Her painting of Tidmarsh Mill, for example, the first house she lived in with Strachey, with its dark waters and lonely swans. And her portraits of the novelist Julia Strachey, Gerald Brenan and EM Forster – as well as that one of Lytton himself, now in the National Portrait Gallery. It’s difficult to separate Carrington from Bloomsbury but on the evidence of this exhibition, her work can also stand very firmly on its own two feet.

Dora Carrington: Beyond Bloomsbury is at Pallant House, Chichester until the 27 April 2025.

Lucy Lethbridge is a journalist and writer. She has written several history books, including, most recently, Tourists: How the British Went Abroad to Find Themselves.

Crop-haired, coltishly boyish, energetically creative and friend and lover of both men and women, Dora Carrington (she dropped the Dora early on and was known simply as Carrington) was the very embodiment of the Bloomsbury Group spirit and the jazzy bohemianism that flourished in the inter-war years. As is the case with so many of the Bloomsberries, Carrington’s biography tends to overshadow her work and she is often viewed as an artist on the edge of the group rather than in the central space her works deserve.

Her life was free-spirited and buffeted and romantic without a trace of sentimentality and often marked by sadness. And her end was tragic. She ran away from her kindly father and a mother who was an enthusiast for martyrdom and respectability, to study at the Slade, just before the First World War, part of the generation of young artists described by their tutor Henry Tonks as ‘a crisis of brilliance.’ Among her fellow students was Mark Gertler, who became her lover and whose paintings at this period (though darker and stranger than Carrington’s) echo hers.

Dora Carrington, Lytton Strachey Reading, 1916, Oil on panel

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Carrington took her prodigious talent for draughtsmanship, modelling and still life out into the world and was soon swept up in the convention-defying and convivial excitements of life in the Bloomsbury Group. And she might (who knows?) then have moved on to different worlds entirely were it not that, while staying with Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant at Asheham in Sussex, she crept upstairs to cut fellow guest Lytton Strachey’s beard off. Legend has it that he opened his eyes and she fell instantly in love. From that moment, Strachey was the lodestone of Carrington’s life. He was gay so their relationship was cosily domestic but non-sexual. She had many lovers and eventually married Ralph Partridge, a writer and sportsman, with whom Lytton was also in love. Their menage a trois (‘a triangular trinity of happiness’), much of it at Ham Spray, their Hampshire house, was a time of great happiness and stability but was shattered when Lytton died in 1932. Unable to continue without him, two weeks later Carrington took her own life. She was only 39.

Dora Carrington, Cat and nude, illustrated letter to Poppet John, 1928.

Dora Carrington, Cat and nude, illustrated letter to Poppet John, 1928.Courtesy of the Dora Carrington Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

A wonderful new exhibition at the Pallant House gallery in Chichester has put Carrington’s art back into the foreground. And not just her paintings but all the teeming creativity that characterised her whole life: her misspelt letters illustrated with wonderful sketches of life at Ham Spray or cartoonish pictures in the margins; the furniture she painted with brightly theatrical scenes; a fireplace decorated with her painted tiles; a trompe l’oeil bookcase filled with books with funny titles (‘Deception’ by Jane Austen being one). She had a profitable sideline making tinsel pictures (in the tradition of Victorian ‘treacle’ paintings) on glass which she sold in Fortnum & Mason – she would feed her guests sweets and hoard the coloured sweet papers. Very few of these pictures have survived but the show’s curators, Ariane Bankes and Anne Chisholm (editor of Carrington’s letters) have scoured the country and come up with some delightful examples, displaying Carrington’s love for popular and folk art, for pantomime, circus, and Victorian ephemera. One of Carrington’s tinsel pictures sold at Bonhams in 2021 for £57,000. She would have been mightily surprised and, I think, amused to know this.

Dora Carrington, Iris Tree on a Horse, c.1920s, oil, ink, silver foil & mixed media on glass, The Ingram Collection.

Dora Carrington, Iris Tree on a Horse, c.1920s, oil, ink, silver foil & mixed media on glass, The Ingram Collection.Courtesy of The Ingram Collection.

Carrington’s paintings are lovely, compelling, sometimes intimate (her well-known portrait of Strachey, his long-fingered hands holding a book to his nose, is here) and sometimes shadowed by a kind of foreboding – such as ‘Farm at Watendlath’, her oil of a white farmhouse in Cumbria surrounded by hills that bear in oppressively. Like Gertler, she was influenced by pub-signs, with their flat, colourful one-dimensionality and this is apparent in many of her portraits: she liked the solid- planed beauty of her housemaid Annie Stiles and painted her portrait several times. And ‘Mrs Box’ is a portrait of the housekeeper who looked after the Cornish house where the Carrington family went on holiday. Foursquare, her hands on her lap, her old-fashioned bonnet surrounding an impenetrable old face, ‘Mrs Box’ portrait seems a remarkable achievement for a 20-year-old.

Dora Carrington, Mrs Box, 1919, Oil on canvas.

Dora Carrington, Mrs Box, 1919, Oil on canvas.Courtesy of The Higgins Bedford.

Known works by Carrington are few – but many are now integral to the visual chronicles of Bloomsbury. Her painting of Tidmarsh Mill, for example, the first house she lived in with Strachey, with its dark waters and lonely swans. And her portraits of the novelist Julia Strachey, Gerald Brenan and EM Forster – as well as that one of Lytton himself, now in the National Portrait Gallery. It’s difficult to separate Carrington from Bloomsbury but on the evidence of this exhibition, her work can also stand very firmly on its own two feet.

Dora Carrington: Beyond Bloomsbury is at Pallant House, Chichester until the 27 April 2025.