Artists’ off-brand Works

10 November 2022

ShareThink outside of the box when collecting big names.

Richard Smyth

Richard Smyth is a writer and critic. His latest novel The Woodcock was published by Fairlight Books in July, 2021.

Success, for an artist, can be both a constriction and a liberation. Success – sales, a reputation – may furnish the time and means to work; it may also, though, fix the artist on rails, so to speak, limiting their creative direction, sapping the will to explore their talents, and setting them on that thankless course: giving the public what they want.In art, of course, a living is a living, and many artists are happy in their pigeonholes. But no matter how strong an artist’s brand – to use 21st-century parlance – there are nearly always adventures, experiments, to be found in their work, if you look closely enough.

LORD GROSVENOR'S SWEET WILLIAM IN A LANDSCAPE

George Stubbs, ARA, 1779 read more at Rountree Tryon Galleries

‘Any artist constantly has to balance between following their creative impulses or continuing with tried and tested territory that they know provides a living,’ says Rowland Rhodes, Associate Director at Rountree Tryon Galleries. ‘If a niche has been found and demand is there, it might seem risky to go in a different direction. On the other hand, artists don’t want to be seen to be standing still and those that manage to successfully evolve and diverge over time are often considered the best.’

Few artists are as closely associated with a specific subject as George Stubbs (1724–1806). From the late 1750s onwards, Stubbs was celebrated as the greatest of all horse painters; his masterpiece Whistlejacket today hangs in the National Gallery, and his Gimcrack on Newmarket Heath fetched £20 million at auction in 2011. But prior to his move to Lincolnshire in 1756, Stubbs had been a jobbing portrait painter in the north of England. Even after fame, there was more to him than horses.

‘In the 1760s Stubbs began to paint more ‘exotic’ animals,’ Rhodes explains. ‘These subjects are perhaps considered secondary to his well-known equine works but were brought into the spotlight in 2013 when his paintings of a kangaroo and dingo were saved for the nation following an appeal from the National Maritime Museum.’

These works were commissioned by the botanist Sir Joseph Banks, who had voyaged in the Pacific with Captain Cook and provided Stubbs with sketches and descriptions of the animals.

‘The paintings are regarded not only important to art but also science and exploration, and it was considered a huge triumph to raise the £4.9 million required to keep them.’

AUTUMN GARDEN WALK

Jonathan Atkinson Grimshaw 1879-80, oil on canvas $445,000 at M.S. Rau

A tidy sum, of course – as was the £6.8 million paid for Stubbs’ Tygers At Play in 2014. It is, however, still some way short of Gimcrack’s £20m, and Stubbs’ ‘exotic’ animals remain obscure in comparison to his equine subjects.

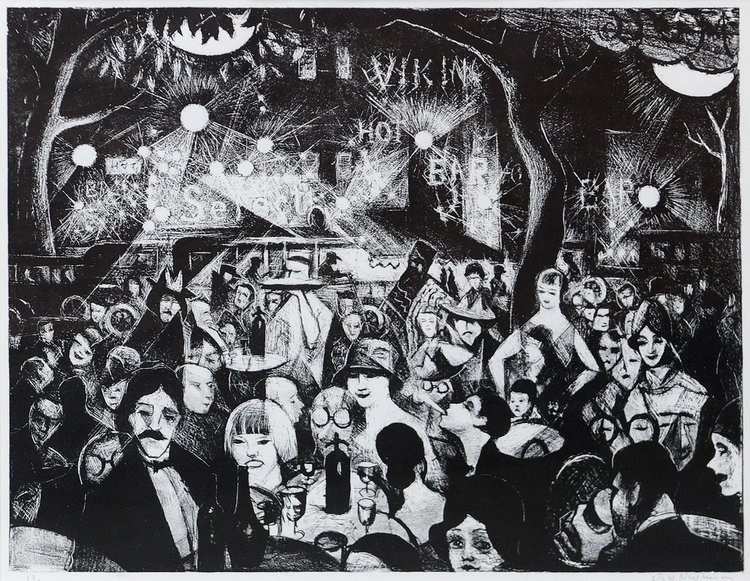

SUR LA TERRASSE

C R W Nevinson 1919-1920, lithograph £22,000 available at Goldmark Gallery

Critical responses to work that deviates from a customary theme can be unpredictable. The reputation of Atkinson Grimshaw (1836–1893), for instance, rests chiefly on his remarkable nocturnal urban landscapes. Less well-known are his handful of ‘fairy’ paintings. Works such as Spirit Of Night and his depictions of Iris, goddess of autumn, showcase Grimshaw’s masterly handling of gloom and luminescence in a new way; there is a different kind of beauty here, and layers of magic and eroticism that are somehow absent from his nocturnes of Leeds and Glasgow. For some admirers of Grimshaw, these works constitute a fascinating excursion; others feel more strongly. ‘It is a remarkably effective and haunting fairy image,’ writes the critic Christopher Wood of Spirit of the Night, ‘and one can only wish Grimshaw had painted more of these, and fewer versions of the Liverpool docks.’

Change, of course, is not always an artistic decision; often, it is imposed from outside, and the artist has no choice but to forge a new path in response. Just as we can imagine an alternative timeline in which Siegfried Sassoon lived out his days as an obscure country versifier, Wilfred Owen as an unknown Keatsian in suburban Reading, so we can wonder in what directions artists such as Frank Owen Salisbury (1874–1962), Paul Nash (1889–1946) and Christopher Nevinson (1889–1946) might have gone, had war not intervened.

‘Many [painters] became official war artists or documented experiences while serving abroad or on the home front,’ says Rowland Rhodes. ‘This was uncommon ground for all, and forced artists in a different direction.’

There is of course a near-infinite range of variables, creative, emotional, social, political, that might push an artist toward a new theme, genre or style. It’s likely, though, that they may have to wait for their less on-brand works to get the recognition they may or may not deserve – and they may be waiting forever.

‘The more famous or collected an artist becomes, the greater the interest is in all the work they made,’ says Rhodes. ‘In many cases, the knowledge and appreciation of ‘off brand’ works is not until after an artist’s lifetime.’